Jan 19, 2024

Japan's onsen in winter, the best season for a soak

Gallery - Why winter is the best time to experience onsen in Japan

It took us a while to work up enough confidence to get our kit off and take a dip in one of Japan’s onsen, or hot springs. Years in fact. Now, we can’t wait to disrobe during a weekend away to soak in scolding waters until our limbs are as loose as linguine. A trip to an onsen in winter has become a regular fixture on our Japan travel calendar.

Yes, winter. For us, Japan’s onsen experience looks and feels best in the snow. Bathing aside, the beauty of the traditional townscapes that are typically the setting for Japan’s onsen “resorts” appears almost haunting after snowfall. And we like nothing more than to soak in the ethereal romance of the setting while in a state of almost passive post-dip torpor.

The imagery is evocative. If you’re looking for the Japan as drawn by Studio Ghibli, perhaps you might find it in an onsen in winter.

We’ve still much to explore when it comes to onsen in Japan. Our winter onsen experiences have largely been limited to those destinations that can be accessed with just a little effort from Tokyo over the course of a weekend.

Maybe some of these images will present a case as to why you should take a trip to one of Japan's onsen in winter.

Kusatsu Onsen, Gunma Prefecture

Our first onsen experience in Japan and a classic.

Kusatsu Onsen can often be found at or near the top of charts detailing the best onsen in Japan. In January the town in Gunma Prefecture topped Japan's Top 100 Hot Springs list produced by Kankokeizai Shimbun for the 21st consecutive year.

Kusatsu Onsen is easily recognized for its yubatake. The steaming, sulphuric-smelling “hot water field” is the source of bathing waters for many of the ryokan here. Waters which are noted for their acidity. “In only ten days, a 6-inch nail left in the hot spring is reduced to a mere skeletal shard,” say the people from guide website Kusatsu-Onsen. We did notice a bit of a post-dip tingle on the skin ourselves.

(The famous yubatake of Kusatsu Onsen in winter, Gunma Prefecture.)

The yubatake also serves as a kind of focal point in the center of the town and is typically illuminated at night.

From the yubatake, narrow streets lead to traditional ryokan and small shops whose structures almost seem to loom over the foot traffic like a medieval townscape. These passages are at their haunting best at night when the foot traffic thins out and the lights from ryokan lobbies emit a melty, hypnotic glow.

(Evening on the streets of Kusatsu Onsen in winter, Gunma Prefecture.)

During our visit, the long staircase leading up to Kosenji temple overlooking the yubatake was, at night, covered with candles.

On the morning of our second day in town we made the easy hike out to Sainokawara Park where we followed a narrow trail through the snow, beyond which bubbled and steamed the area’s hot spring waters.

Ikaho Onsen, Gunma Prefecture

Another hot spring in Gunma Prefecture, Ikaho Onsen is perhaps most famous for centering on a long stone stairway, or “ishidan.” All 365 steps of it, on the slopes of Mt. Haruna. It’s a striking sight and a curious centerpiece, even if it does place the lightest attempts at a stroll around town at risk of becoming something of a heart-thumping lung buster.

You can tackle the staircase sections at a time though, perhaps pausing to enjoy the retro game centers that are a fixture of Japan’s onsen towns - think pellet-gun rifle ranges and old-skool pinball machines, among other Japanese equivalents of “fun at the fair.”

During a February visit the snow around Ikaho and its staircase could be described as little more than a dusting, if that. A testament perhaps to the town’s relative ease of access from Tokyo.

At higher altitude though, beyond Ikaho Shrine which marks the end of the staircase ascent, some of the snow had settled during our visit and we were able to enjoy suitably wintery scenes around Kajika Bridge, the brilliant vermillion of which looked marvelous against what snow there was.

(Ikaho Onsen stone staircase and Kajika Bridge in winter, Gunma Prefecture.)

From Ikaho Shrine we followed a trail further up the mountain to the forest parks and observation points on Mt. Haruna. In the brilliant, clear winter light the trees glistened with ice and snow even if underfoot we’d have struggled to make much of a snowball.

Shibu Onsen, Nagano Prefecture

Our favorite onsen in Japan in winter thus far.

We took the train out from Nagano Station and became giddy with anticipation as we climbed our way between snow-covered fields to the station at hot-spring town Yudanaka Onsen. From Yudanaka it’s a 30-minute walk further up the Yamanouchi Valley to Shibu Onsen.

Yudanaka and Shibu Onsen sit on an important pilgrimage route between Kusatsu Onsen in Gunma Prefecture and Zenkoji temple in what is now downtown Nagano. The locals here have been welcoming weary travelers for hundreds of years, and they’ve been blessed with some of Japan’s finest onsen waters to do it.

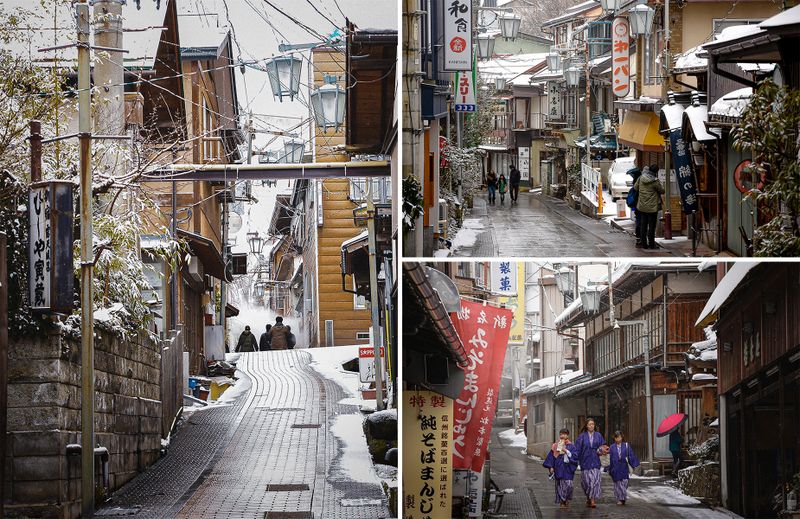

Shibu Onsen sometimes appears to have been frozen in time, and is all the more charming for it, particularly in winter.

(The streets of central Shibu Onsen in winter, Nagano Prefecture.)

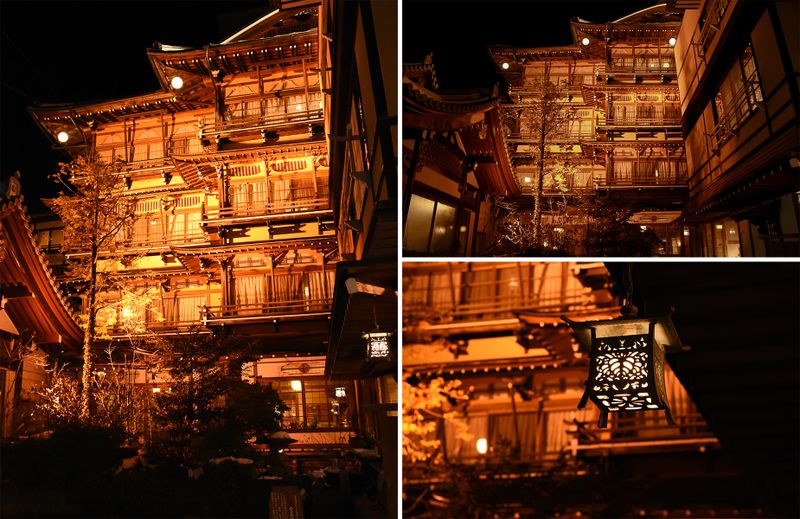

What action there is in town centers around the impossibly charming and narrow alleys hemmed in between the Yokoyu River and the valley walls. In this warren of streets is the centerpiece of Shibu Onsen’s time-stopped charms, the ryokan Kanaguya.

Displaying the kind of fantastical imagination that could reduce the creatives at Studio Ghibli to tears of envy, Kanaguya is almost hard to contemplate such is the tangled beauty of the structure.

Established some 260 years ago as a blacksmiths (Kanaguya translates to “hardware store”), a landslide laid waste to the original structure leading the owners to rebuild it as a blacksmiths-cum-onsen ryokan. Why not?

(Exterior of ryokan Kanaguya in the hot spring town of Shibu Onsen, Nagano Prefecture.)

We also enjoyed Shibu Onsen for its cafes and eateries offering nice coffees, cakes and other treats including dinner options. They’re aimed at the skiers and snowboarders who use the town as their base, but it’s nice to feel that you have options outside of the traditional Japanese dinner served at your ryokan.

Exciting trails and pathways sneak between secretive temples and shrines on the valley sides north of town. They look magical in the snow.

Shibu Onsen is also a base from which to visit the famous bathing monkeys at Jigokudani.

Yunishigawa Onsen, Tochigi Prefecture

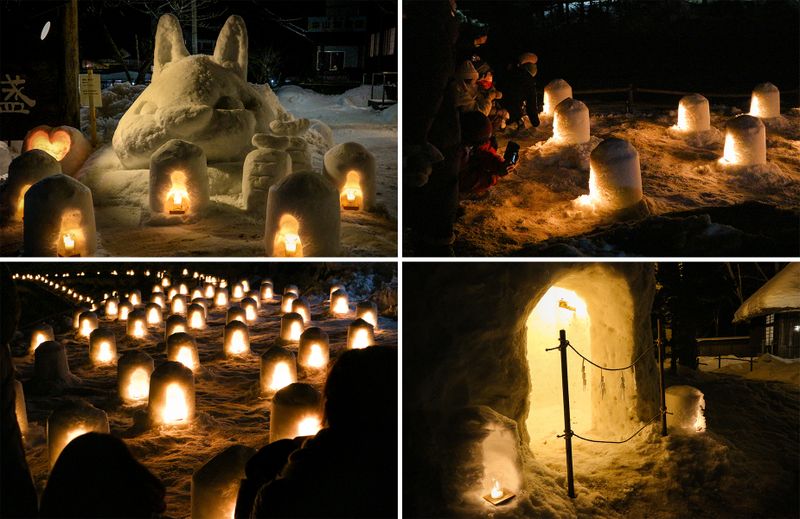

There was no shortage of snow at Yunishigawa Onsen in Tochigi Prefecture during a February visit. More than enough for locals to sculpt the hundreds of kamakura snow houses for an annual festival which sees the houses lit with lanterns to bring a warm glow to the otherwise freezing evening temperatures along the banks of the Yunishigawa river.

Yunishigawa Onsen is said to have been founded by members of the Taira clan who sought hiding in the remoter regions of Japan following their defeat during the Genpei War in the late 12th Century. They picked a nice, quiet spot up here among the mountains of Tochigi Prefecture.

(Remote and quiet Yunishigawa Onsen makes for a wonderful onsen destination in winter.)

These days though, you can reach town by bus from Yunishigawa Onsen station - even if it might mean a frigid wait beside snow drifts outside the station building.

For the most part Yunishigawa was as quiet as a mouse during our visit and the town lacks much of a center or focal point. Overnight onsen visitors should go half or full-board at their ryokan or risk going hungry as outside eating options appear very limited here.

Outside of the kamakura festival most of the foot traffic could be found at the Heike no Sato village - an open-air museum featuring homes and other artifacts depicting early life in the area.

(Kamakura snow houses lit up for a winter festival in Yunishigawa Onsen, Tochigi Prefecture.)

Very cold, lots of snow, and lots of walking meant that an onsen soak at Yunishigawa really hit the spot. So much so that post-dip we didn’t have the strength to make it up the stairs (or even get to the elevator) back to our room. We had to take a break in the lounge en route.

Yunishigawa Onsen could be combined with the much larger and more popular (if more faded and peeling) Kinugawa Onsen.

Onsen tips for the reluctant bather

If you’re a little reluctant to take a dip with strangers in one of Japan’s onsen, maybe some of these tips will help you to feel more at ease during a hot spring trip.

Go in winter - Arguably when the onsen experience is at its most rewarding. The uncompromising cold should also make the prospect of a hot bath, even with strangers, more appealing.

Take a room with an ensuite shower or bath - A case could be made that the ensuite shower or bath of a room in an onsen ryokan is one of the more lonely looking places in Japan. Even now though, we find it reassuring to know that we have the option to at least get clean in the privacy of our own bathroom. On the other hand, perhaps not having the option is what we need to get us in that onsen.

Look for options with a kashikiri “private bath” - Many onsen accommodation options will have one or two private baths which can be rented by overnight guests (solo, or with partners and family), usually for around 40 minutes at a time. Some places offer them free-of-charge, other places may command a fee. In our experience they’ve usually been atmospheric outdoor baths and well worth seeking out.

Go at the right time - At more tech-savvy onsen accommodations you might find on the TV or even a tablet device in your room, or via a QR code to scan with your phone, online information telling you how busy the baths are. When they’re telling you that the baths are not busy, it's not unusual to have them to yourself, or if not, with maybe just one other bather.

Without this service you can always ask at the front desk about the conditions.

If you’re having dinner as part of your ryokan package, you’ll likely be offered a choice of two times as to when it is served. Select the later time and head to the onsen baths while the early diners are being served. Everyone likes to take a dip just before dinner and it’s probably fair to say that most onsen ryokan guests are of a more senior vintage and like to take dinner earlier.

Another good time might be just after check-in, which tends to be at 15:00, when many guests may still be out exploring the area or will be taking time to settle into their rooms.

If no other indicators are available, it’s almost always the case that shoes or accommodation slippers have to be removed at the entrance to the onsen area (before you even get to the changing rooms). And it’s very often the case that you can see if slippers or shoes are present and thus how many people you can expect to be using the baths.

Read up on the rules and how-to guides - Perhaps for many reluctant onsen bathers it’s that first time in combination with the clothes off aspect that can present a hurdle hard to overcome. And maybe it’s all this talk of how-to guides and rules that actually makes the onsen experience appear more complicated than it really is. Because it isn’t.

Anyway, the guides are out there and over the years it's been noticeable the increasing number of ryokan offering explanatory material in languages other than Japanese.

More images of Japan's onsen in winter on our Insta:

Do you have a favorite onsen you like to go to in winter in Japan? Share your experiences in the comments.

0 Comments