Jul 1, 2021

Concerns raised over residence card checker app released to public

An application developed by the Immigration Services Agency of Japan to check the authenticity of residence cards held by foreign nationals has sparked anger and concern that it could be left unchecked, leading to division and discrimination.

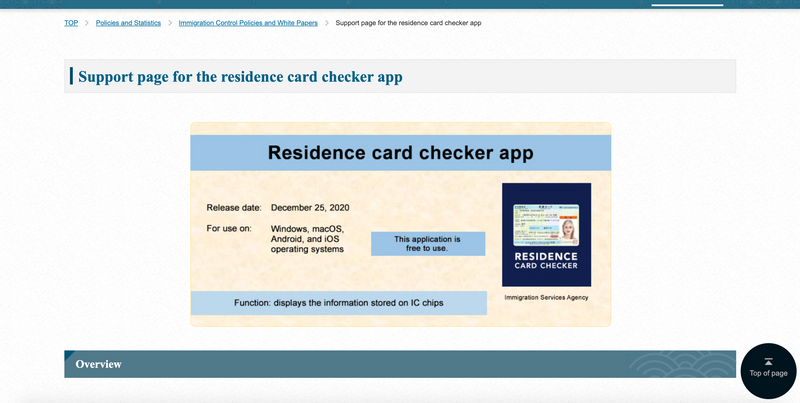

With the Residence Card Checker app (在留カード等読取アプリケーション) installed smartphones can be used to read and display information stored on the IC chip stored within residence cards, held by mid-to-long-term foreign residents of Japan, to reveal whether or not the card has been forged.

(Screen shot from the Immigration Services Agency of Japan website)

While the app is largely aimed at employers in Japan considering hiring foreign workers, as well as at financial institutions for identification checks, it can be downloaded for free with no restrictions on its use other than the technical specifications required for installation.

Following its launch in December 2020, the Residence Card Checker app has been downloaded around 40,000 times as of May this year, according to the Immigration Services Agency.

Despite being available to download for over half a year, recent images of a poster advertising the app spotted in Tokyo and shared on social media have sparked outrage among some foreign residents.

“Are they expecting ordinary Japanese folks on their way to work to check random “foreign” looking people?,” wrote one user on Twitter.

Concerns over the potentially discriminatory nature of the app are not being voiced by foreign residents of Japan alone.

“I'm very skeptical that the immigration agency felt the need to go out of its way to create a checking system like this and distribute it to the general public,” said Eriko Suzuki, from the NGO Solidarity Network with Migrants, speaking at a parliamentary roundtable on refugee issues held in May.

“It encourages discrimination and prejudice in daily life. Is this what the agency should be aiming for? I think it will hinder the performance of an inclusive society,” she said.

During the roundtable Ryo Nishiyama, a manager from the agency’s immigration information systems department told roundtable attendees, including members of the House of Representatives and media, that the app had been developed at a cost of 83 million yen. When questioned about whether not during its development consultation with lawyers and groups relating to Japan’s foreign communities had been sought, Nishiyama responded that no such consultation had been sought and that there were currently no plans to do so.

In addressing concerns about privacy, it was stressed that the IC chip in each residence card only stores that information which is displayed on the face of the card itself and that all the agency’s app does is display the same information to prove that a card has not been forged.

“Of course, regular people who can proudly show their (identification) cards, are all good people who would say, “please, take a look,” (when asked),” said Nishiyama, drawing what appeared to be a reaction of shock from some.

According to National Police Agency statistics relating to organized crime in Japan, in 2019, 748 arrests were made relating to forged residence cards.

Without available data to show how many similar arrests have been aided by the use of the agency's app since its launch however, concerns were raised over why the app had been downloaded 40,000 times, by whom and for what purpose.

"Foreigners, in particular those who are working, are in a really weak position, so rather than it being down to them not to show their card if they don't want to, you should have thought about those cases where people were forced to show their cards," said one attendee of the roundtable addressing agency representatives.

While the agency’s Residence Card Checker app does not enable users to save the information it displays, it isn’t the only residence card-checking app on the market in Japan.

The development of similar apps by the private sector was raised as a point of serious concern during the roundtable.

In some cases, apps developed by private companies not only offer users the ability to read a residence card’s IC chip but also enable the information, including the image of the card holder, to be saved and organized on the user’s smartphone. Another app is offered as part of a larger foreign employee management system allowing users to save and manage residence card information on a cloud, with email alerts sent out to both employee and employer ahead of the expiration of status of residence.

Rather than arming employers in Japan with an ability to check for forged residence cards held by potential foreign employees, it was suggested during the roundtable that a greater problem lies in employers being unaware of the types of status of residence available to foreigners and the scope of work it enables them to pursue.

This lack of awareness could lead to stiff penalties for employers.

According to a translation of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act employers having foreign workers engage in work illegally, knowingly or otherwise, face penalties of imprisonment “with work” for up to three years and / or fines of up to three million yen.

Cases where both forged identity and negligence during hiring procedures combine, however, perhaps only serve to cloud issues surrounding card-checking apps.

In June two former employees of Uber Japan Co. were referred to prosecutors for allegedly hiring two Vietnamese who had overstayed their status of residence as staff of the Uber Eats delivery service. The former employees were suspected of hiring the Vietnamese workers without checking their status of residence.

It was reported by local news that one of the Vietnamese registered with the Uber Eats website using a false identity -- someone else's residence card -- according to the police.

Would an app like that developed by the Immigration Services Agency and others have helped to prevent the above from escalating into a situation involving staff referred to prosecutors? Without knowledge of status of residence or a willingness to check its period of validity in the first place, perhaps not.

If the combination of forged cards and negligence serves to only confuse this issue however, the combination of pressure from above and ignorance or poor taste has the potential to deliver something of alarming clarity.

In June it was reported that an illustration posted on the website of the prefectural government of Mie in relation to the illegal employment and illegal stay of foreigners was removed after it was judged to have been inappropriate.

The illustration pictured what appeared to be three workers -- a construction worker, entertainer, and factory worker -- with grey skin, yellow eyes and expressions that appear to smirk, each holding a sign reading phrases like, “unqualified for status of residence.”

According to news reports, the prefectural government’s public relations division had said the illustrations were requested by local police and were posted to match the period of an “Illegal Employment of Foreigners Countermeasure Campaign” by the Immigration Services Agency.

While the agency’s Residence Card Checker app may primarily have been created to aid employers and save them from potential penalties, in itself a noble end, the app has the appearance of being an attempt to pass the buck of responsibility by authorities who might be better to invest time and money in educating the employers their app is trying to support.

An app for employers though isn’t the real issue at hand. Opening up such a tool, largely unchecked and targeted toward a vulnerable minority, for public use and allowing the private sector to spawn its own, and in some cases, more capable versions seems to have been recognized as the more significant concern here. It’s a recognition that is perhaps as just as it is unfortunate.

After all, even in the hands of those whose job it is to serve and protect we’ve seen in the example above how pressure to deal with matters relating to foreign residents can lead to something ugly and potentially vilifying of the vulnerable and the innocent.

If the roundtable in May is anything to go by though, Japan’s foreign residents can hear at least some voices of support.

Video footage of the roundtable (the 24th General Assembly of Parliamentarians on Refugee Issues / 24回難民問題に関する議員懇談会総会) is available on YouTube and was the source for this article's corresponding content.

It should be noted that, based on the footage, the Immigration Services Agency representative fielding questions from parliamentarians and media during the roundtable appears to be filling in for their superior(s) who appear to have turned down an invitation or request to attend.

Related:

Plans to better COVID vaccine support for foreign residents of Japan late in the day?

0 Comments