Nov 12, 2021

What to expect from the ningen dock, Japan’s warts and all health check

*Article updated following receipt of ningen dock results.

You’d be forgiven for hearing the term ningen dock (人間ドック), “human dock,” and imagining some scene from a dystopian future.

Ningen dock really is a spectacularly awful, not to say anything about it being alarming, name for what might be more prosaically referred to as a “comprehensive medical check-up,” or other terms to that effect.

A recent first-timer to Japan’s ningen dock experience, the reality revealed itself to be somewhere in the middle -- myself and fellow dockers did shuffle in dystopian silence, wearing matching pastel gowns, around a medical facility in between being plugged into various bits of kit to be jabbed, prodded and scanned. The retro slippers, a faded and peeling facility, and friendly nurses were anything but dystopian or futuristic.

Dystopian because of geography, perhaps? Where I’m from, the idea of laying prostrate and offering up our most private parts for the judgment of a faceless system -- even if it is free-of-charge -- only to have the results printed out in some unknown office by some unknown hand and posted to us two weeks later sounds, well, like a spectacular reduction of the individual and an invasion of privacy. Doesn’t it?

Many Japanese people though, are by now used to joining the queue, urine sample in hand, for some kind of medical once-over. It’s par for the course for the average company worker over here to file through an annual kenko shindan, lit. “health diagnosis” -- the “ningen dock light,” if you will -- covering the basics of blood pressure, chest X-ray, and BMI among other checks that can be done in the space of an hour or so. In fact, provision of a kenko shindan is a mandated responsibility of employers, according to Japan’s Industrial Health and Safety Act.

What is a ningen dock?

The much more involved ningen dock dates back to the early 1950s when the Japan Hospital Association came up with the “short-term inpatient comprehensive physical examination” -- later to become the ningen dock after being labelled as such in a newspaper article -- the first of which was carried out on July 12, 1954 at what is now the Center Hospital of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine in Tokyo.

According to schedule records of the Center Hospital, early ningen dock were carried out over a period of six days, covering over 40 checks.

The examination soon spread to hospitals across Japan and in 1959 the Japan Society of Ningen Dock was established, initially as an organization to train staff in how to carry out the examination.

July 12 is now (not very well) known in Japan as “Ningen Dock Day” -- a bid to promote health through early detection of potentially serious medical conditions through the medical examination.

Ignorance is bliss?

I’m perhaps the epitome of the reluctant docker. Again, perhaps it’s geography, with my reluctance rooted in having grown up in a society where problems are largely dealt with when or after they occur, rather than placing an emphasis on preventing them from occurring in the first place.

“Here’s a chance for you to get something out of your health insurance.”

The words of my Japanese partner, apparently in accordance with this country’s penchant for joining the queue to anything being handed out at a discount or for free, even if they don’t particularly want it.

“And it’ll be lucky if they catch something early.”

Again, the partner. This time almost sounding excited at the prospect.

Over the years in Japan I have undergone a number of kenko shindan. When I was teaching in public schools here an annual tuberculosis check was mandatory, usually in the form of a chest X-ray. I was still nervous about a ningen dock though. Not the procedures. Just the results.

“I’m skeptical about them,” said a doctor at a private clinic in Tokyo I once went to following a “recommendation” to do so -- the result of a kendo shindan, which turned out to be a false alarm.

The doctor was expressing their concern about the level of personal care and meaningful doctor-patient relationship with things like a kenko shindan or ningen dock, the lack of which together with the sometimes production-line nature of such checks, they felt, can lead to misdiagnosis and unnecessary stress. Or maybe the checks were bad for business.

Perhaps a greater level of intimacy can be achieved when taking a ningen dock with a private medical facility. Or depending on the program. Facilities often offer a choice of programs, from half-day checks to courses carried out over two or three days, like one might have expected from a spa retreat. Expect prices to start from around 50,000 yen.

On this occasion, rather than a private out-of-pocket job, the ningen dock was financed to the tune of all but 1,200 yen by social insurance, or “shakai hoken,” which offers the examinations (heavily subsidized) annually at select medical facilities.

The first step was to share insurance details with one of said facilities and book an appointment through them. Facility and insurance provider then communicated and took care of the necessary (subsidy) payment. Paperwork about the ningen dock -- questionnaire, explanations, maps, examination content -- was then posted out by the medical facility.

Preparing to dock

Three items that required some preparation prior to taking the ningen dock:

Medical questionnaire - all in Japanese and, for me, requiring assistance to fill-out. The questionnaire also provided a chance for me to select four from a number of health conditions that I had concerns about. I’m not really sure what this would have led to -- whether it be some form of consultation on the day or just to provide greater context for the examiners. I didn’t select any.

A section of the questionnaire also asked if there were any lifestyle changes that one was planning to undertake, or in the process of undertaking. I answered that there were -- cutting down on sugars and snacking before bed.

Urine sample - kit provided, sample to be taken from the first toilet visit on the morning of the ningen dock. It involved an origami paper cup, suction tube, and test tube.

Stool sample - two, ideally to be taken within three days prior to the ningen dock (four or five if you can’t produce on such demand). Kit provided - place sheet of paper over the toilet basin, do your business onto that, dip a kind of stick into it to get a coating, then insert that into a kind of test tube. It’s as unpleasant as it sounds. Samples to be kept in the fridge.

(Instructions for taking a stool sample, part of a kit sent out in preparation for taking a ningen dock.)

There are other prerequisites that come with the ningen dock, as one might be familiar with from other medical checks. They include things like not eating on the day of the examination (prior to it), not drinking within two hours prior to the examination, and no alcohol the day prior, among others.

On the day of the examination there was little messing about at the medical facility (which appeared to be a facility dedicated purely to such examinations), perhaps thanks in no small part to COVID-19 prevention measures.

Reception - handover documents, health insurance card, and pay money.

Change into medical robes - in a locker room (with no one else), strip down to nothing but your underwear (take socks off), get into the robe and slippers, place your stuff in the locker and keep the key around your wrist like you might at a swimming pool.

After this the attentive nurses guided me to and from each of the checks. I was never left alone and at no point did I feel confused about where I was supposed to be or what I was supposed to be doing. Each test was conducted in private, away from prying eyes.

The examination ended with a consultation with the resident doctor. What results they were able to confirm on the day they went over with me very briefly -- I could see some of the results on the doctor’s clipboard and my chest X-ray image on the wall.

Now, the consultation might have lasted longer had there been any points of concern. I was given the all clear though and even though I was asked if I had any concerns myself, I had none and so the consultation lasted little more than a minute or two. At no point was the “lifestyle changes” I had detailed on the questionnaire referred to during the consultation.

I was then handed laxative pills (more on that later), a bottle of water, and a 1,000-yen coupon card to use at a variety of stores across Japan.

The end, after what was probably around two hours.

What tests are included in a ningen dock?

The content of the ningen dock taken on this occasion is listed below. I’ll largely refrain from going into the purpose of the tests in any great detail as I’m in no way qualified to do so.

内科診察 (naika shinsatsu) - doctor places a stethoscope on your upper half and listens to something

身体検測 (karada kensoku) - weight, height, BMI

腹囲 (fukui) - waist measurement

視力 (shiryoku) - vision

眼圧 (ganatsu) - intraocular pressure check (the one with the gentle blast of air into your eyes)

眼底 (gantei) - fundus examination (look at the dot of light)

聴力 (chouryoku) - hearing test

血圧 (ketsuatsu) - blood pressure

肺機能 (hai kino) - lung function (but in the end didn’t do this, because I don’t smoke?)

胸部X線 (kyobu X-sen) - chest X-ray

胃部X線 (ibu X-sen) - sometimes referred to as the “barium swallow,” an imaging test to check inside gut, stomach, others

心電図 (shindenzu) - electrocardiogram

腹部超音波 (fukubu chou onpa) - abdominal ultrasound

血液検査 (ketsueki kensa) - blood test

尿検査 (nyou kensa) - urinalysis (urine test)

便潜血 (bensenketsu) - test for blood in stool

Of the tests undertaken the “barium swallow” experience (胃部X線 / ibu X-sen) perhaps bears closer inspection, first of all because it involves exposure to radiation and drinking down the chemical element, barium.

Now, I placed myself in the hands of my partner (a medical professional) with regard to this, as the potential risks of taking this test were explained in advance via an information sheet that came with the appointment confirmation and pre-check questionnaire, very little of which I could read and / or understand. This perhaps harks back to the doctor’s concern about the lack of meaningful doctor-patient relationship.

That aside, the experience itself was, in retrospect, hilarious and involved getting tipped about on a gurney while a nurse in the other room barked out instructions with military zeal via a speaker system -- turn over twice, hold on tight, no burping, take two tissues (not one or a few, but two).

Getting the barium out the other end, so to speak, proved to be less hilarious even with the help of the laxative pills handed out at the end of the examination.

For now we await the final results of the ningen dock which will be sent by post in two to three weeks.

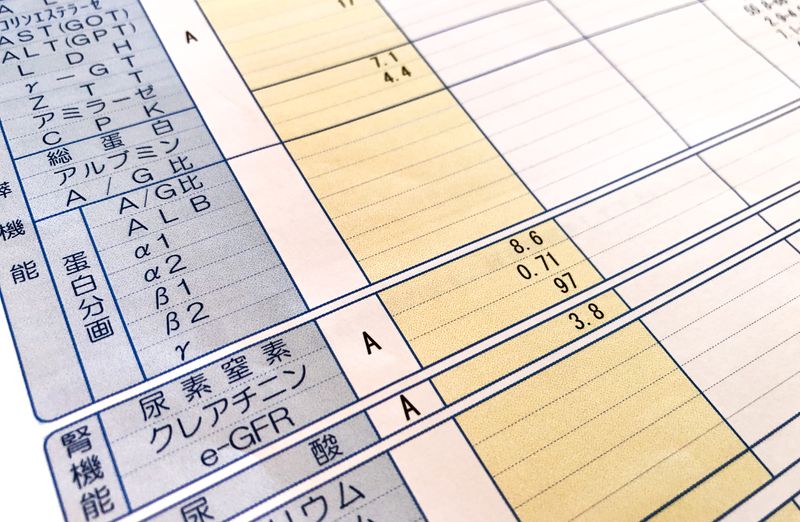

[UPDATE] The results of the ningen dock dutifully arrived in the post two weeks to the day after having undergone the examination.

The result package contains a breakdown of how to read said results -- in Japanese and far more than this expat can handle, despite being a reasonably fluent speaker.

The results themselves occupy four sheets of A4 paper (one-sided). Results for each test are graded thus: A, B, C, C1, C2, D1, D2 and E. Grades are shown along with the actual data results of the tests.

I won’t go into the conditions of each grade in significant detail for fear of being misleading. It could also be the case that systems of grading vary between institutions.

Very roughly though, in the case of the institution used here, “A” means no abnormalities detected (within the scope of the testing), “B” is a result slightly outside of normal but nothing requiring of action, “C” grades represent some sort of follow-up of your own is needed -- for example, changes in diet, lifestyle -- with results to be checked again after one year (C), six months (C1) or three months (C2). “D” and “E” grades require further testing and / or treatment.

Despite being graded with mostly A’s and the odd B, I did get one C. As a result my overall grade was also C - at least that’s the logic that I’m following.

A space for free text on the results sheets is used by what I assume is a doctor to detail any recommended or required course of action. I got one line stating that something is a bit high and recommended actions in my daily life that I should pursue in order to deal with the issue -- stamped with the seal, or “hanko,” of approval from the doctor.

And that’s about it.

Would I do it again? Well, according to that “C” grade I should be getting that particular part of my makeup tested again after one year, but I could just get a single test for that rather than going through the whole ningen dock extravaganza again. That said, the receipt of a (largely) clean bill of health (within the scope of testing) has perhaps given me the kind of confidence I had been lacking in order to stay on top of this kind of testing. Whether or not that confidence is still with me in one year’s time remains to be seen.

If you have any experiences you'd like to share about Japan's ningen dock or kenko shindan, please do so in the comments below.

Related articles on City-Cost:

How Much Does Dental Care Cost in Japan?

Taking a JAPANESE HEALTH EXAM: Kenko shindan & ningen dock:

0 Comments