Jul 4, 2019

Summer in Japan

Where summer in some parts of the world comes with it a sense of light and carefree freedom, by stark contrast summer in Japan is greeted by many with a tired sense of sweaty dread -- even just thinking about the season’s incredible heat and humidity can be enough to exhaust many.

[VIDEO] Summer in Japan: 5 things we love about Japan's sweaty season

When is summer in Japan?

On the homepage of the Japan Meteorological Agency an overview of the climate in Japan details summer season in Japan as covering June, July and August. According to this model then, summer in Japan gets off to a damp start with the rainy season, also known as tsuyu, -- the result of an annual meeting between cool and warm masses of air -- which brings plenty of overcast skies and damp days (and potentially torrential and dangerous rains in some parts of the country) starting from around mid-May in Okinawa and lasting until the end of July in Japan’s northern regions (from Tohoku and further north).

For most people living in Japan though, the rainy season and summer season are treated as two distinct entities. As well they might, as the characteristics of each appear to differ significantly and feel that way for many.

No, in more common parlance, when people think “summer in Japan,” minds are concentrated on the end of the rainy season through to the end of August, even though for many the first half of September can also feel like summer.

The traditional summer season curtain raiser in Japan is Ocean Day -- umi no hi (海の日). Ocean Day is a national holiday “celebrated” in Japan on the third Monday in July. As far as celebrations for Ocean Day go, they tend to be pointed towards the opening of the nation’s beaches, something referred to by the Japanese as “umi-biraki.” Not that the beaches in Japan are ever, in principal, off-limits, but Ocean Day marks the first day of certain sections of beach being patrolled by lifeguards. Lifeguards stay on duty across the beaches of Japan until around August 31, or the last weekend of that month (which may blend with September 1).

In fact, it’s by observing Japan’s beaches at this time that one can get a good sense of how seasons in Japan are approached as being so distinct by the Japanese -- temperatures are often still perfectly suited to spending time at the beach in early September, but as soon as those lifeguards have packed up for the season the beaches see an exodus of bathers on an almost Biblical scale, not to return until Ocean Day the following year when the summer season in Japan, and thus the time to go to the beach, “officially” starts.

Heat and humidity

For many, summer in Japan means heat and humidity on a tangible scale that can be hard to put into words, the brunt of which is felt by eastern and western Japan -- Eastern Japan: Kanto (inc. Tokyo), Hokuriku (inc. Kanazawa), Tokai (inc. Nagoya) / Western Japan: Kinki (inc. Osaka, Kyoto), Chugoku (Hiroshima), Shikoku, Kyushu.

In fact, while agency data reveals mean temperatures during summer (July and August) across many cities in these regions as being in a relatively comfortable-looking range of around 26 - 28 C this would be to turn a blind eye to climate anomalies in recent years in Japan.

During a prolonged heat wave in 2018 (that was felt across most continents of the Northern Hemisphere) Japan clocked its highest ever temperature -- 41.1 C in the city of Kumagaya, Saitama Prefecture, near Tokyo.

Kumagaya has a reputation as being one of the hottest places in Japan but the heat wave in 2018 saw other cities in Japan top 40 C, Nagoya among them -- a commercial and industrial center in Aichi Prefecture and one of the largest cities in the country.

In fact, it’s really only the higher altitudes and Japan’s northernmost main island of Hokkaido that are spared the brutal heat and humidity that comes with summer in Japan.

Record-breaking temperatures aside, it’s not at all unusual for temperatures in urban centers across much of Japan during the summer to top 30 C. This combined with a monthly mean relative humidity (July and August) that has ranged in recent years in parts of Japan from around 70 - 80% (sometimes over) makes performing even the lightest of tasks feel like a huge hassle. And this is really the essence of summer in Japan for many.

In such conditions even being stationery can feel exhausting but when you’ve got to drag yourself off to work or do the daily chores, well, life during the summer in Japan tends to be structured around how long or how far until the next oasis of air conditioning. The situation is exacerbated when we consider that Japanese society makes few attempts to adjust its pace and style to suit the climate and the human condition -- there is no culture of the siesta here.

Despite the heat and humidity of the summer season in Japan it’s not unusual to see locals (typically middle-aged and elderly women) wrapped up head to toe in track suits, gloves, hats, visors, and sporting sun umbrellas as they look to fend off the sun in order to maintain an image of having porcelain white skin.

Dangers during summer in Japan

Our attempts to make light of the awful heat and humidity of summer in Japan perhaps reflect a default self-defense mechanism that suggests this as the best way to cope. However, the dangers presented by the summer season in Japan are not to be treated lightly.

In recent years the height of summer in Japan has been marked by media reports of people being taken to hospital with heat-related illnesses, as well as reports of fatalities.

During one particular week of the heat wave that hit Japan in 2018 over 20,000 people were taken to hospital with 65 of them dying -- record-high figures since 2008 (when comparable information became available). Most victims of Japan’s summer tend to be the elderly.

Natsubate and nechushou

Perhaps the way many people feel the summers in Japan is captured by the term “natsubate” -- summer fatigue that leaves people feeling, well, fatigued. Natsubate can also come with a loss of appetite, lack of sleep, and a tendency to become irritated (if the energy is still there). On a more serious level, natsubate can manifest itself in the form of diarrhea and spells of feeling dizzy or lightheaded.

During summer in Japan you’ll often hear appeals from the people around you and the people on the TV towards taking care not to get “nechushou,” heatstroke, which can occur should the warning signs delivered by summer fatigue not be addressed appropriately.

Common preventative measures against heat-related illnesses including replenishing water and salt, and staying cool. More comprehensive and authoritative information regarding health during the summer in Japan should be sought elsewhere -- perhaps with the resources available at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Related to summer fatigue, while Japan or the Japanese seem reluctant to make comprehensive lifestyle changes that would be more in keeping with the season, the commercial sector keeps the nation’s shelves well-stocked with a myriad of cooling solutions for the summer season in Japan, from sprays and wipes to sweat-wiping and breathable clothing and bedding. On a serious note, in urban Japan at least, one is never far away from a vending machine or convenience store from which water and other hydrating drinks can be purchased for around 150 yen for a

It’s not unusual during summer in Japan to see the custom or culture of uchimizu being practiced on the nation’s streets and outside of shops -- the sprinkling / splashing of water on the ground to cool things down and keep dust at bay.

Government initiatives like “Cool Biz,” during which office workers are encouraged to dress a little more casually to suit the conditions (stopping some distance short of shorts and t-shirt), have eased the hardship of workers in Japan, to a degree.

Typhoon

According to data from the Japan Meteorological Agency (between 1981 - 2010) the typhoon that made an approach to Japan during this period occurred between April and December, with those making landfall in Japan occurring between June and October. The average number of typhoon to make landfall in Japan between the years above was 2.7 annually.

Anyone who’s been living in Japan over recent years though will likely feel that this number seems rather low although this might be a kind of illusion created by coverage of typhoon that approach Japan (an annual average of 11.4 between 1981 - 2010), the vast majority of which though, don’t make landfall.

The brunt of those typhoon that do make landfall in Japan tends to be felt in the south, on the Okinawa islands as well as Kyushu. There are exceptions though and typhoon can potentially affect any region of Japan.

At their worst typhoon that make landfall in Japan can be disastrous and it always pays to be vigilant during their approach and (possible) landing. Away from southern Japan though, they are more often than not felt like a wet and very blustery few hours of weather, although any travel plans during their passing may well have to be put on hold, if not changed altogether.

Coverage of an approaching typhoon by the authorities and media organizations in Japan is extensive. When it looks to be a large one some TV channels will have round-the-clock coverage flashing and beeping around the edge of the TV screen. Even those people who aren’t literate in Japanese would be hard pressed not be made aware of an approaching typhoon of significant size -- “#Japan” will likely turn something up.

Japanese summer foods

The taste of summer in Japan is served up in a number of seasonal dishes and staples, many of which are said to combat summer fatigue often by way of being easy to digest.

Hiyashi chuka: The Japanese love ramen so much they’ve even created a cool version of the noodles and soup dish so as they can keep slurping throughout the summer without breaking into a dangerously dehydrating sweat. This is hiyashi chuka -- chilled ramen noodles swimming in a tare sauce, often topped with thin slices of cucumber, carrot, ham and strips of omelette. Even if you’re not a fan of ramen, you’ll likely find this easy to stomach.

Eel: Or unagi. Packed with vitamins and protein -- a great source of energy to combat summer fatigue. Unagi is expensive though and the Japanese have been eating too many of them meaning numbers are often low.

(Unagi a traditional summer food in Japan)

Watermelon: Think summer in Japan, think watermelon. When they’re not being smashed to a pulp on the nation’s beaches, watermelon (suica) are being sliced up and skewered on sticks to be served as a summer staple to a thirsty public with an appetite that can just about handle food as solid as this.

Kakigori: A summer-festival staple, kakigori -- shaved ice doused in sweet sauce -- is this country’s equivalent of a cheap 99 ice cream cone served out the side of a neighborhood roving ice cream van. Or maybe it was until the Japanese discovered that Taiwan was taking shaved ice to a whole other level, and one that keeps the flavor beyond the first few sucks / spoon fulls. Still, kakigori remains a summer festival / event staple in Japan.

Nagashi somen: We add this summer food reluctantly because it serves up more novelty than it does summer fatigue-beating nutrition. Somen -- wheat-flour noodles -- are poured into cold water running down a bamboo slide and are plucked out by those with enough energy (and chop-stick dexterity) to be dipped in a soy-based sauce and scoffed. Nagashi somen is more of an outdoor activity than a legitimate source of a meal, although some restaurants in Japan (particularly in Kyoto) do have the kit to handle it indoors.

Summer culture in Japan

Despite the energy-sapping heat and humidity, summer in Japan still puts people in a celebratory mood. There are a number of forms, traditional and modern, in which Japan’s summer season celebrations are manifest.

(Samba dancer at the Asakusa Samba Carnival in Tokyo's Taito Ward, an event seen by some as marking the end of the summer season in Tokyo)

Traditional

Summer matsuri: While rural Japan tends to hold its traditional festivals -- matsuri -- in the autumn to mark the annual harvest, traditional festivals in urban Japan often take place in spring and summer.

By traditional summer matsuri we are referring to those summer festivals that often feature traditional floats, mikoshi (portable shrines) and traditional dance. Scale varies dramatically, from festivals that echo through the streets of an otherwise quite local neighborhood to those that take on the scale of the rock festival, attracting visitors from across Japan and around the globe.

Whatever the scale though, Japan’s traditional summer festivals deliver certain staples -- robust grilled / greasy festival food (yakitori, yakisoba, hotdogs et al), locals in traditional garb (yukata, happi), and lots of booze.

Some of the larger-scale summer matsuri to look out for across Japan:

| Festival | When | Where |

| Gion Matsuri | throughout July | Kyoto |

| Tenjin Matsuri | late July | Osaka |

| Aomori Nebuta | early August | Aomori |

| Yosakoi Festival | mid August | Kochi |

| Awa Odori | mid August | Tokushima |

Tanabata festival is often seen as an early indicator of summer in Japan. Beginning in some parts of the country in early July, tanabata (or sometimes star festival) celebrates the meeting of two love-struck deities who are only permitted to do so once a year -- during tanabata.

Many celebrations for tanabata are actually fairly sedate and largely limited to people writing wishes on memo paper which is then hung on some bamboo. Colorful, and sometimes large-scale, streamers known as fukinagashi are used as tanabata decorations by those towns and groups looking to make a festival of it.

Large tanabata festivals are held in Sendai, Hiratsuka (Kanagawa) and Asagaya (Tokyo).

Summer fireworks festivals -- hanabi

The greatest consensus regarding when fireworks displays started getting set off in Japan seems to point to the early years of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s reign (which began in 1603).

While fireworks displays were seen as a bit of summer relief by the higher-ups who lived in Edo (now Tokyo), one of the country’s largest hanabi events, Sumida River Fireworks Festival, was first held in 1733 as an occasion for people to pray for the souls of those who had fallen victim to a famine and then plague the previous year.

These days fireworks festivals are a well-established fixture on the summer-in-Japan calendar. To this writer’s knowledge they are all held on a pretty large scale (the Sumida River Fireworks Festival attracts nearly one million visitors).

Most hanabi events take place on the banks of large rivers with fireworks being set off from barges or platforms on the river waters. Shows last for around one hour but due to their popularity and the scale of the crowds many people pitch up early, lounging on grounds sheets and eating / drinking the wares hawked at stalls that line the approach to the river.

Be warned that train stations serving hanabi events can get uber crowded, particularly when the event is a wrap.

The spirit of Obon

The mid-August Obon festival appears as a national holiday with many people in Japan heading to their hometowns to bond with the spirits of ancestors which are believed to visit the homes of living family members during this time. The festival is marked by lanterns hung on the doorways of homes to guide the spirits in their return.

While many people are on holiday at this time (with some companies having a fixed week of vacation) Obon (or O-Bon) isn’t actually a national holiday. That said, overseas visitors to Japan at this time may find seats on long-distance public transport harder to come by. Conversely, better deals maybe available for high-end hotels in major cities across Japan as management look to offset empty rooms left by people heading to rural hometowns.

A Buddhist festival, public Obon celebrations often revolve around dance with everyone invited to join in -- deities, spirits, schooled dancers, and casual observers (including you). Dance moves, while probably finely nuanced, appear simple enough that most people can at least have a go! Simple stages are set up in parks and town squares around which the dancing takes place under rows of hanging lanterns.

Modern

(Sun sets over another day at the Fuji Rock Festival in the mountain resort of Naeba, Niigata Prefecture - Image: t.kunikuni Flickr license)

Beach life

As was touched upon earlier, summer in Japan (from Ocean Day in mid-July to the end of August) is also beach season in Japan.

During this time popular beaches, especially those accessible from urban centers, attract Biblical crowds of the great unwashed. If your image of going to the beach is something akin to the high-end stylings of a Saint Tropez then a visit to a popular beach during summer in Japan will come as something of a shock. This is buckets and spades and inflatable ring territory, only in tropical heat. Oh, and the water does feel like champagne on a first dip.

What can be most shocking is the disregard many beach goers during summer in Japan seem to have towards keeping beaches and the immediate ocean clean. It appears to be of little concern to most.

That aside, a visit to the beach during the summer season in Japan can be fun with many stretches of sand playing host to temporary beach bars and eateries. The beaches southwest of Tokyo, in Kanagawa Prefecture’s Shonan region are well-known for having an extensive beach-bar set up (that can sometimes turn raucous).

Suikawari is a popular game played on Japan’s beaches during the summer. It involves attempting to smash a watermelon, laid out sheets or card on the sands, using a stick while blindfolded. Should the resulting mess be edible, it’s passed around and consumed.

Questionable style, roving youths on nampa patrol (“nampa” -- Japanese for flirting / seduction), garbage, and epic crowds aside, the beaches during summer in Japan present few hazards and most are well-patrolled by lifeguards, with special areas for swimming.

Typhoon are an obvious beach-going hazard. Japan sees very few shark attacks although beaches have been closed in summer due to sightings off the coast of hammerhead and other dangerous sharks as recently as 2015. The backend of summer on some beaches in Japan can see jellyfish and stingray.

Despite the often smoggy / grey skies during summer in Japan, the sun is strong and those with fair skin will likely burn without adequate protection.

Summer music festivals

Japan’s summer music festival scene probably can’t compete with North America and Western Europe but the summer season in Japan does see a number of large-scale outdoor music events set up shop. Fuji Rock Festival and Summer Sonic are the established heavy hitters with festival organizers typically able to attract A-list artists from overseas each year.

Dance extravaganza Ultra has been making a stop in Japan since 2014. Held in Tokyo’s Odaiba district, the mid-September timing probably pushes the boundaries in terms of this being a summer music festival, but the temperatures would suggest otherwise.

It’s a beer garden, but not as we know it

Japan’s summer season beer gardens probably enjoy something of a love-hate relationship among the punters, and should probably come with a warning for the first-timer for whom the term “beer garden” conjures images of wooden benches in the green and pleasant grounds of a quaint countryside boozer.

In Japan, swap those grounds for an urban tower-block rooftop on which a few potted plants are what constitutes the garden (but really do little other than to block any potentially fine city-scape view.)

Yes, many of Japan’s beer gardens are set up on the rooftops of department store buildings in the city, making them tricky to spot. Most beer gardens in Japan operate on an all-you-can-drink / eat basis -- expect to pay 3,000 - 5,000 yen for two hours of binging and don’t expect much in the way of quality.

The atmosphere of Japan’s summer beer gardens tends to be simple and robust, enough to put some people off them entirely. In light of this, an increasing number of more sophisticated beer gardens have been popping up across Japan in recent years.

Beer gardens in Japan tend to open between June and September.

Essential summer-in-Japan experiences

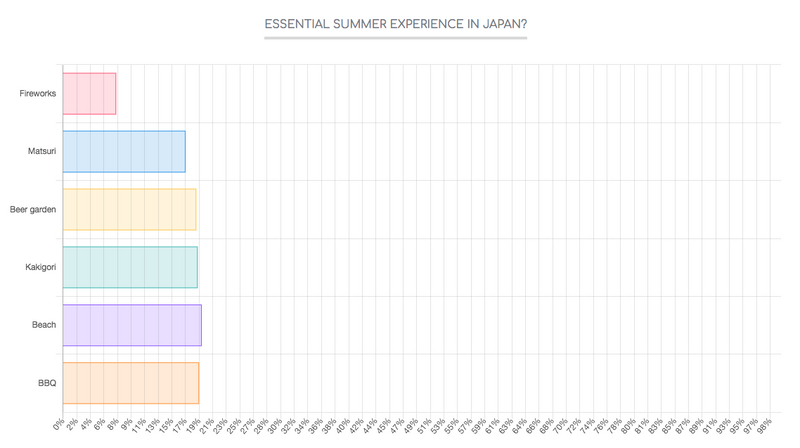

We conducted a quick poll regarding essential summer experiences in Japan via our POP SURVEY on City-Cost. The results were as follows …

Essential summer experiences in Japan, in rank order:

| 1 | Beach |

| 2 | BBQ |

| 3 | Kakigori |

| 4 | Beer garden |

| 5 | Matsuri |

| 6 | Firework |

Summer critters

If the taste of summer in Japan is captured by some of the foods listed above, the sound of summer in Japan is perhaps best (or unfortunately) represented by cicadas -- “semi” in Japanese.

At their peak a scratchy chorus of Japan’s cicadas can drown out all other sounds -- even going it solo they can make a din. When heard from a distance though, on a balmy summer’s evening they are the sound of the sultry tropics.

Unfortunately, semi are big, ugly and have little control over their movement when airborne. And for some people (this writer included) they can be genuinely terrifying. The worst of their horror presents itself when they appear dead on the ground only to suddenly find a new and uncontrolled lease of life upon your approach. Give them a wide berth, although they are not dangerous.

The good news is that semi only live for about one month after emerging from their underground habitat (where you’ll never notice them). Above ground they hang about in trees.

The bad news is that when they do take flight they seem to have little control, bumping into walls, settling on your apartment mosquito guard and often lying on their backs on your balcony (shooing them off of which is not an experience for the weak of heart)!

Children like to try and catch them with nets and ogle at them in their insect collection boxes.

Mosquitos

Summer in Japan sees its fair share of mosquitoes. Living in Japan during summer one shouldn’t be surprised to be kept awake at night due to the blood-sucking presence of one or two. Any apartment in Japan worth its salt will be fitted with mosquito screens over balcony doors and most (if not all) windows. They break easily though and poor fitting can often leave gaps. Having a stock of mosquito coils to hand (readily available in Japan) is a good idea.

Malaria was eradicated in Japan in the early 1960s. Any cases in the country these days are imported by overseas travelers.

In 2014 Japan saw its first outbreak of dengue fever (spread by mosquitoes) in nearly 70 years with over 20 confirmed cases, originating from a park in central Tokyo, of all places.

Hornets

Japanese hornets -- “suzumebachi” in Japanese -- are huge and horrible. Active through spring to autumn, while not an everyday sighting one shouldn’t be surprised to see at least a handful (hopefully not literally) during the summer, even in urban areas of Japan.

Trouble with suzumebachi tends to come when their basketball-looking nests are disturbed.

Where deaths occur it tends to be due to allergies to the venom. (This writer used to work in a jr high school in Japan to which suzumebachi were regular visitors. If a student was stung once, they would be taken to the nearest clinic promptly. Teachers needed to be stung twice in succession to get similar treatment. Make of that what you will.)

If you see a Japanese hornets nest, give it a wide berth. If you come close to a hornet that is airborne, staying calm seems to be the best advice. Hornets like the chase, apparently, so running away isn’t advised.

Cockroaches

Cockroaches -- “gokiburi” in Japanese -- are frequent visitors to homes and apartments during the sweaty summers in Japan.

Japan has a myriad of sprays, traps and poisons readily available in stores to deal with them, none of which make a cockroach encounter any less skin-crawling.

Summer summary

While there can be little doubt that for many people, summer in Japan is more endured than it is lived, in its finer moments the summer in Japan is capable of delivering sensations and experiences that leave a lasting impression, in a good way.

From those dips in the ocean when the water feels like champagne, to breathing in the cool air of a mountain resort, Japan’s sweaty summer lends itself to some life-affirming highs. And then there are the balmy summer evenings, the atmosphere thick with exotic Asia, makes everything seem as one, and the cicadas’ chorus turns from din to tropical rhythm.

0 Comments