Feb 3, 2021

Beyond the shadows: Exploring Mizuki’s manga world in Chofu, Tokyo

The work of legendary manga artist Shigeru Mizuki is known throughout Japan and beyond. The world he created and the names of the characters that populate it have become household on these shores and his influence felt across the globe, from the jungles of Papua New Guinea to awards committees in Europe.

Following the trail of Mizuki’s widespread appeal brings us back to the city of Chofu, Tokyo, a city that has adopted the moniker, “Mizuki manga’s birthplace.” Here we explored the relationship between Mizuki and his created worlds, and the real world of Chofu where he was resident throughout his career, to discover that the two are intertwined in ways that blur distinction.

©Mizuki Productions

(Shigeru Mizuki in the city of Chofu, Tokyo)

“I think that yokai exist.”

“Where are they?”

“Yokai are in the dark places, the places where not much light can reach. Maybe places like shrines. Maybe,” speculated Etsuko Mizuki, the youngest daughter of legendary manga artist Shigeru Mizuki.

We were in the offices of Mizuki Productions in central Chofu, the city where Etsuko’s late father lived for the duration of his years as a creator of manga in a career which spanned over half a century and told a myriad of stories featuring yokai -- spirits and monsters from Japanese folklore -- the most celebrated of which made Mizuki a household name in Japan, GeGeGe no Kitaro.

With the sun shining bright outside the visible presence of yokai appeared limited to the covers of the volumes of Mizuki’s manga -- “Mizuki manga” -- that lined the shelves of the office meeting room, as well as in the figurines sat atop many of the surfaces. They even adopted a more international flavor by the entrance, taking the form of wood-carved tribal masks, souvenirs from Mizuki’s globe-trotting yokai research.

©Mizuki Productions

(Etsuko Mizuki in the offices of Mizuki Productions, Chofu, Tokyo)

The daylight hour and the dangling prospect of “maybe” though, was enough to see me head back across town to Chofu in order to explore the city after hours in the hopes of a yokai encounter, perhaps among the locales that Mizuki reimagined with his creative hand as the setting of a number of scenes in his manga.

A Chofu City official had pointed me in the direction of one such location -- Fudatenjin-Shrine --which in the world of Mizuki manga features in a volume of Hakaba - Kitaro (Kitaro from the Graveyard), "The Weird One," in which Kitaro -- our yokai hero called upon by humans to deal with the more troublesome of his kind -- is said to live in the forest behind the shrine. (“Hakaba - Kitaro” was the original name for what became the manga “GeGeGe no Kitaro.”)

Standing on the approach to the shrine's main hall, ancient Fudatenjin certainly appears in a suitably otherworldly mood with nature’s lights switched off and the soft glow from electric lamps casting unfamiliar shadows across the shrine grounds to hide who knows what.

Nothing to be scared of though. The yokai of Mizuki’s world aren’t here to cause fright, and their world was created here in Chofu. Perhaps echoing how the chief protagonist in GeGeGe no Kitaro seeks to find harmony between humans and his fellow yokai, Mizuki portrayed yokai in such a way that they could be accepted by everyone.

Although that acceptance is proving difficult given that I can’t see them. Maybe I’m not straining into the shadows hard enough. Or with enough imagination?

“For Mizuki, yokai were really like friends or family. He felt close to them,” Etsuko told us back at the Mizuki Productions office.

“So he believed in their existence, too?”

“Yes. If he didn’t think so, maybe … well, it’s thinking in this way that enabled him to create his manga.”

Perhaps I lack enough belief and the yokai enough darkness. The city and its lights appear to creep ever closer around Fudatenjin-Shrine and the forest out back, imagined or otherwise, has given way to Tokyo’s yawning western suburbs. A few times I’m joined in my search by office workers stopping by for prayer on their way home. When Mizuki moved into town from nearby Shinjuku over half a century ago much of Chofu was nothing but fields.

While the yokai might be proving elusive at Fudatenjin, thanks to Mizuki many people have been able to feel closer to them. Mizuki’s yokai, along with his stories, have likely been seen, read, watched and celebrated in Japan by something close to “everyone.” It’s impossible to be definitive, but you’d surely have a hard time finding an adult in Japan who hasn’t heard of Shigeru Mizuki or interacted with one of his creations, knowingly or otherwise.

“The existence of yokai is something that has been talked about for a long time in Japan and there are many people that know about this so I think this is why it has been able to reach a lot of people,” Etsuko said, speculating on the roots of Mizuki manga’s popularity, which spans generations and demographics to this day.

“Mizuki took information (about yokai) that existed only in academic papers and images and through manga introduced yokai in a way that everyone could easily understand,” added Tomohiro Haraguchi of Mizuki Productions.

You read that right, “academic papers.” In the early stages of our interview Haraguchi had looked me straight in the eye and asked, “How much do you know about yokai?” Implicit in the asking was the uncomfortable truth that there is far more to know about yokai than the paucity of knowledge with which I had armed myself ahead of the interview. I was given a crash course which included reference to the likes of Kunio Yanagita and Inoue Enryo, 19th-20th century pioneers of research and thought about yokai. Today in Japan there are universities that have departments of folklore with students and faculty conducting research into yokai.

While the Japanese and the yokai may have a shared history that I don’t, I wonder if either party has picked up on the irony that just a short hop from Fudatenjin-Shrine’s quiet location in the receding shadows the lights of Tenjin-dori -- a stretch of Chofu’s eateries, watering holes and local stores -- shrine bright and in their glow sit colorful statues of Mizuki’s yokai, that may even be said to bask in the street’s cheerfully lit and unashamed retro fun.

The setting could be fitting too, though -- if Mizuki wanted his characters and yokai to be approachable, well, here they are, under the lights in one of the most salt-of-the-earth and unpretentious spots in the city.

The statues along Tenjin-dori are but one of many tributes to, and celebrations of, Mizuki manga that can be found dotted throughout Chofu. Seeking them out might be one of the delights of a visit to a city which calls itself “Mizuki manga’s birthplace.”

Not to be confused with Sakaiminato in Tottori Prefecture, the western Japan city where Mizuki was raised, “Mizuki manga’s birthplace” Chofu is where the manga started, made a household name of the characters, and ended over 50 years later with Mizuki’s death on November 30, 2015 at the age of 93.

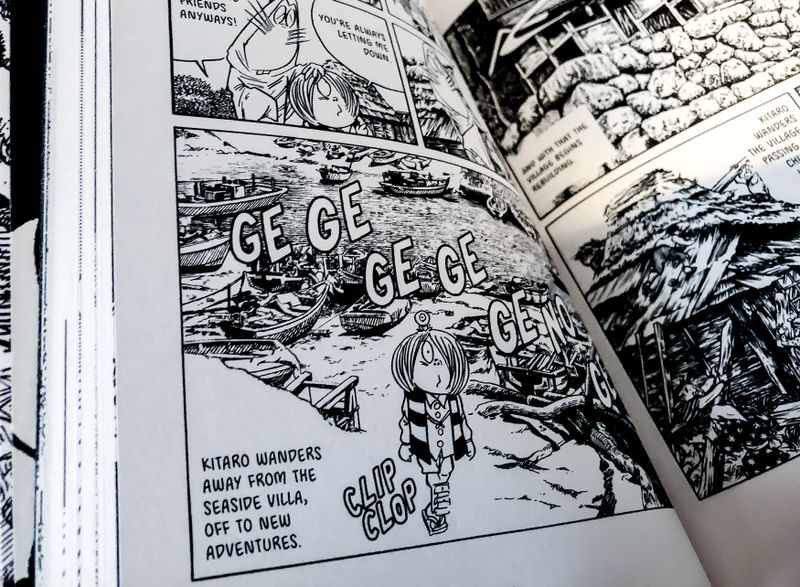

©Mizuki Productions

(Scenes from Shigeru Mizuki's manga GeGeGe no Kitaro)

Today the city of Chofu, which coined the “Mizuki manga’s birthplace” phrase, and Mizuki Productions collaborate to showcase elements of Mizuki’s work through events, themed parks, and even a themed city bus, among other initiatives.

“We cooperate together on this so that even after all this time, we can say that there was a person called Shigeru Mizuki, and what kind of person he was, and have people continue to read the manga he created and remember who he was,” Haraguchi explained.

“We can’t do this alone, so to have the city of Chofu think in the same way and come up with such ideas, we are so grateful for this.”

In late November team City-Cost was present at the location of one such initiative, Kitaro Square, during the city’s annual GeGeGe Ki.

A days-long celebration of the life and works of Shigeru Mizuki held around the anniversary of his passing, GeGeGe Ki sees a number of events held around Chofu, centering on a stage set up in the city’s broad station-front plaza.

Kitaro Square plays host to a Mizuki manga-themed cosplay event and on the bright autumn day the square’s stationary art objects representing yokai and other characters that appear in GeGeGe no Kitaro and other of Mizuki’s works were joined by an animated gaggle of Mizuki manga fans in cosplay, and team City-Cost sporting yellow and black striped “Kitaro” vests.

©Mizuki Productions

(“Kitaro” cosplayers Yurina (far left) and Koryu (far right) during the GeGeGe Ki event, Chofu, Tokyo)

“I heard a lot about yokai from my grandmother so I’ve been familiar with the world of Kitaro since I was child,” explained cosplayer Yurina Arai (32) who was attending the event for the third year, this time dressed as Neko Musume, the cat-girl yokai from the GeGeGe no Kitaro world.

“When I did something wrong my parents would tell me, "Yokai will come and get you and Kitaro won't come to help.” I used to think of yokai as being scary, but now not at all. I’m fascinated by them.”

Standing next to Arai’s Neko Musume was Kitaro himself, cosplayed by Koryu Shimizu (27).

Shimizu might be considered proof that the efforts of the city and Mizuki Productions to introduce the world of Mizuki manga to new audiences do bear fruit.

“Actually, I wasn’t so familiar with GeGeGe no Kitaro. I moved to Chofu four or five years ago. GeGeGe no Kitaro is featured in a number of places around Chofu, so I’ve had many chances to interact with it and I’ve become more and more fascinated by it,” she explained.

Arai, however, had the experience of seeing the creator of her beloved characters in person, going about his life in Chofu.

“Before he passed away you would see him quite often here and there, at coffee shops, and he would go out to drink with his daughter.”

“Even though he was this amazing manga artist he would appear quite normal with his daughter. This makes his world feel very close, for me. He was such an amazing person so I would think how amazing it was to see him out drinking coffee in such places.”

Arai’s encounters are shared by other residents of Chofu who can recount seeing Mizuki riding his bike to and from the office, stopping to fuss over children, even in the bookstores leafing through the pages of his own books.

It seems that while Chofu’s shadows may keep Mizuki’s yokai hidden, the man himself was very much out in the open. “A familiar celebrity,” as one resident put it.

It was pleasing, as well as somewhat of a relief, to find that the connection between Chofu, “Mizuki manga’s birthplace,” and the man behind it all is real and felt by people on the streets here, rather than just an exercise in overzealous but ultimately empty marketing.

Such connections aren’t always so welcome though. Etsuko tells us of how she suffered at the hands of classmates at school on accounts of her father’s work.

“I wasn’t particularly aware of (my father’s work, his fame) but my classmates at school would say things to me about it. Sometimes they would use it to make fun of me. They would say that what he was writing about were lies. I didn’t like it when they said things like that.”

“I mean, it was a world that you couldn’t see with your own eyes, you know?”

There are some dots, however, between Chofu and Mizuki that on the surface at least seem hard to connect. Chofu the city and Mizuki the Chofu resident -- open, cheerful and full of colorful character -- appear a world away from the World War II battle grounds of Papua New Guinea and Mizuki the reluctant soldier stationed in the country while serving in Japan’s Imperial Army.

“He didn’t just create manga about yokai, he also created manga about war. “Like” is perhaps not the right term, but the manga about war left an impression on me,” came Etsuko’s answer when asked if she has a favorite story among her father’s manga.

We were talking about the 1973 manga, “Soin Gyokusai Seyo” (English title - Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths). Mizuki’s damning and terrifying account of the terrifying stupidity of men with military authority gone mad in the jungle has arguably left the greatest impression on overseas readers, too. Soin Gyokusai Seyo saw Mizuki become one of only three Japanese manga artists to be awarded the Heritage Award at the Angouleme International Comic Festival, one of Europe’s largest.

Of course, the experience of war and suicide charges in the southwestern Pacific nation left the greatest impression upon Mizuki himself.

“I can’t explain very well but I think it had a profound influence on him, his manga,” Etsuko said.

“It changed him, from prior to going to war and then after.”

“There are lots of stories in which the bad yokai are killed but in the Kitaro manga the bad yokai are persuaded to return from where they came instead of having them killed. This comes from (Mizuki’s) experiences during the war, seeing his close friends die, seeing death up close, he decided he didn’t want there to be killing in his stories,” Haraguchi explained.

But not before leaving us with the devastating climax of Soin Gyokusai Seyo in which the words of the last man standing in his final throes echo a profound warning, “Guess everyone died feeling like this. No one to tell … just slipping away forgotten. With no one watching.”

It's perhaps a testament to the man, his talent and mental fortitude that in both life and work Mizuki could make the switch from the darkest depths of the human condition to the cheeky humour of a yokai notorious for their pungent flatulence (GeGeGe no Kitaro’s “Nezumi Otoko”).

Perhaps it was Chofu, far removed from the jungle and deadly conflict, that was able to provide an environment in which Mizuki felt able to describe his WWII experiences. Not that even here he seems able to have escaped the horrors entirely.

“Whenever I write a story about the war, I can’t help the blind rage that surges up in me. My guess is, this anger is inspired by the ghosts of all those fallen soldiers,” wrote Mizuki in 1991 in an afterword published in an English-language edition of Soin Gyokusai Seyo.

(The English-language edition of Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths which we read in preparation for this article was published by Drawn & Quarterly and in its fourth print since hitting the shelves in 2011. We found it easily enough in a Tokyo bookstore along with other English-language translations of some of Mizuki’s more popular manga, from the same publisher. In case you end up wondering, the delightfully cheeky humour is loyal to the source material.

Despite Mizuki’s giant reputation in Japan, translation of Mizuki manga into other languages (or English, at least) has been a relatively recent undertaking, but it’s one that appears to have been welcomed by Mizuki and Etsuko.

“It’s a nice feeling. My father was pleased, too. He was like, “Yokai are spreading throughout the world,” Etsuko said during our interview.)

The Koshu-kaido, that great historic avenue rumbling east-west between Tokyo and Kofu (Yamanashi Prefecture) runs right between Fudatenjin-Shrine and Tenjin-dori, separating the two as if a symbolic border between different worlds -- one of quiet and shadows and Chofu’s hidden possibilities, the other of the city’s brash bright lights, of life lived out in the open.

Walking west along the avenue, away from Fudatenjin, the Tokyo traffic races by on my left and beyond that an army of tired office workers pours out of the train station and into the restaurants, bars and bright lights. To my right sprawls in silence a great swathe of suburban Tokyo -- at night a silent world of narrow lanes between homes and neighborhood temples and shrines where the dark is interrupted by the lonely glow from living room windows. It’s here in this world where Mizuki now rests, in the cemetery at Kakushoji Temple.

On my way to see Mizuki I sneak through a gap between houses and into the grounds of Shimoishiwara Hachiman Shrine. In any other circumstance I might not have given the small shrine a second glance, probably shrugging it off as “just another shrine in Japan” to hurry along with the rest of my life.

In the hands of Mizuki though Shimoishiwara Hachiman presents a different prospect. The shrine is portrayed in some of his manga as the place where GeGeGe no Kitaro’s Neko Musume lives, under the eaves of the main hall.

Despite dangerously close to being middle aged I’m (quietly) excited like a child as I explore the grounds alone, taking in the exotic shapes and scrutinizing the shadows for signs of yokai activity.

I’m not sure what I should be looking for, and maybe there really is nothing to be found. Or maybe I’ve missed the point? Etsuko’s words echo, “a world that you couldn’t see with your own eyes.”

So then artists like Mizuki see for us and, in his case, create the visual elements of illustrations in manga like GeGeGe no Kitaro. More than this though, the artist creates magic and with it gifts us a sense of wonderful possibility. They fill the air with the electric excitement of new worlds for us to run free in.

The air of Mizuki’s world is charged in Chofu, and I’m here running free in my search for the yokai.

This article was supported by Chofu City.

0 Comments